Counting Consciousnesses

In this post, I will share preliminary thoughts that I have about consciousness, and in particular counting consciousnesses. The TL;DR is that (maybe) a single brain contains many different, coexisting but distinct consciousnesses. And if this is true, one surprising corollary is that sperm whales might have exponentially more consciousnesses than all other animals combined, and therefore morally we ought to focus mostly on reducing their suffering.

This theory is is still half-baked, and I’d appreciate criticism and comments.

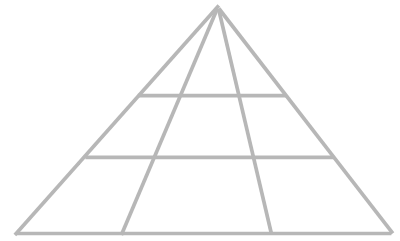

Let’s start with a puzzle you are likely familiar with: How many triangles are in this figure?

The answer is 18, as you can convince yourself. Here we highlight two of them:

Notice that these two triangles overlap - they share part of their perimeters. So, why was it justified to double count the shared parts? Why are we “allowed” to ascribe the same line to two different triangles?

The answer is - we are allowed to do whatever we want, but we typically choose to do what is practical or makes most sense to us. In our case, it is quite obvious that the question “how many triangles?” presupposes that double counting is valid and encouraged - otherwise the puzzle becomes much less interesting.

Let’s move on to the next question: how many cars do you see in this image? (image source: Wikipedia).

The answer is 1. But, I will now claim that this is not the only possible answer, and we chose it mostly for practical reasons.

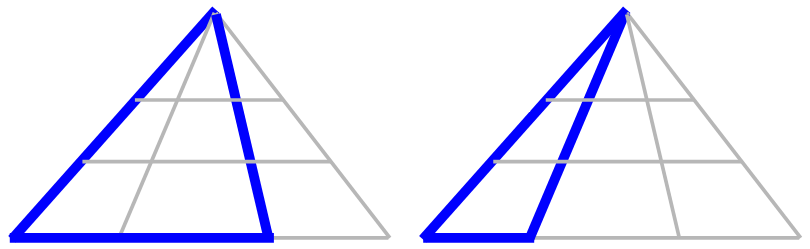

Have a look at the following images, which are modified versions of the original image:

In these modified images, we masked-out small parts of the original. I ask the reader to view the modified images simply as a subsets the original image, with some parts excluded (not erased) from from the original.

The two modified images are still images of cars. These cars are completely embedded in the original image. And the two cars are not identical - they are mathematically different subsets. So, wouldn’t it be fair to say that the original image includes these cars as well, bringing the car count up to 3? True, the three different cars have a very large overlap, but so did the triangles in the first puzzle, where we allowed double counting.

More generally - given a car (not an image of car) - we can take many different subsets of its atoms or other constituent parts, and this subset can still be considered a car. If we had a function which takes as input a physical configuration of atoms or particles and the function returns whether this configuration is indeed a car, then we can apply it on many different subsets of the given car and it would output “car”.

We see that given a “single” car, there is some sense in which we actually have countless different cars. So why did we answer “1” to the original question “how many cars”? Because for all practical purposes, we have only a single car. All of these countless cars are very strongly related - they always move together, they are always owned by the same person, they have the same mileage. Therefore, it makes a lot of practical sense to treat all of these cars as one.

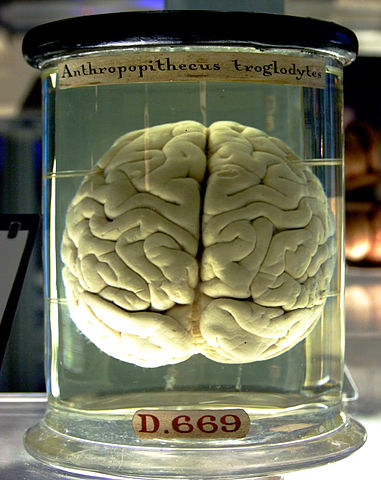

Now we ask how many brain are in this image? (image source: Wikipedia)

From the previous considerations, we already know the answer: Even though we can argue that the number of of brains is very large by considering all the different subsets, for practical purposes the number of brains is 1, because these brains all control the same body, always move together, etc.

However, there is an important aspect in which brains might be different from cars: consciousness. Assuming that brains give rise to consciousness, then can we say that different subsets of a brain have distinct consciousnesses? This question is important for practical reasons, because we might base our moral philosophy and behavior on the axiom that we should minimize the total number of of suffering conscious entities. Therefore, we should asks ourselves how to count conscious entities. Does one brain contribute only one consciousness?

There is some reasoning which suggests that maybe indeed we should consider each brain as giving rise to more than a single consciousness.

Consider the Gazzaniga and LeDoux experiments done in the 70’s. From what I understand, in this experiment, brains of patients were split into the two hemispheres, disconnecting any neural circuitry between them. Using the fact that the brain’s left (right) hemisphere processes the right (left) visual field, the researchers were able to feed sensory input to each hemisphere separately, without information leakage between the two parts. From the results, it seemed as if each hemisphere had its own consciousness.

OK, but what happens when the brain is not split? We only have a single consciousness, right?

I’m not sure. True, it feels like we have one consciousness, but this might be a “looking under the streetlight” fallacy. Another option is that still, each hemisphere has a separate consciousness. Moreover, each subset of the brain might have a separate consciousness. But since most of these subsets share most of their information processing, they are mostly conscious of the same stuff. They all exist simultaneously and might all be under the illusion that they are the only consciousness around, and that they control the body in which they are embedded, and they are all equally wrong.

I acknowledge that I didn’t really make an argument here in favor of the multiple-consciousness-per-brain hypothesis over the alternative. The point is mostly that, this is an option that should be considered.

Another point: Suppose that we have a perfect theory of consciousness. One of the products of this theory might be a function \(f\) which takes as input a physical configuration (for example, a segment of spacetime together with the quantum state of the quantum fields), and it returns the “amount” of consciousness that emerges in this configuration (if that makes any sense). If we apply \(f\) on a very small subset of the brain, which is composed of, say, only 100K neurons, then \(f\) might return a small non-zero number. If we apply \(f\) on a large subset of the brain, we will probably get a large number, because this subset posses a “strong” consciousness. Can we say that these two subsets poses the same consciousness? I don’t think so, because one subset is much more conscious than the other, so how could they be identical? The conclusion is that the brain has multiple consciousnesses.

Or consider a computer running an algorithm. A widespread approach to consciousness is that any information processing procedure, if it is sufficiently complicated (and in the right way), will give rise to consciousness. The algorithm might be a very large artificial neural network (NN). NNs are typically built from layers, each layer processing information fed from the previous layer and feeding it to the next layer, until the final result is obtained in the last layer (We assume here a feed-forward NN, without recurrent feedback). Suppose that this NN is conscious, and is very deep, i.e it has many layers. Now, consider the set of all computations that this NN does, excluding (i.e ignoring) the last layer. Does this subset have consciousness? probably, because it performs the vast majority of calculations that the original NN does. But is it the same consciousness as the original NN? probably not, because it omits a small but important piece of the processing. It might be a bit less conscious. So, we get that the NN contains multiple embedded consciousnesses, and they share units of calculations.

So, maybe it is still reasonable to count the number of brains in the last image as 1, but we might want to consider how we count the consciousnesses that emerge in the brain. Admittedly, it’s very strange to think that I share my body with multiple other consciousnesses and that we are unaware of each other. In fact, who is “I” in the previous sentence? A suggestion is to think of this “I” as the body which wrote this post, as controlled only by the deterministic laws of physics. As a bi-product, multiple consciousnesses emerged which all believe that they are “I”.

One possible implication of the multiple-consciousnesses-per-brain hypothesis is that we should all put our efforts mostly into reducing suffering of sperm whales. To see this, note the mathematical fact that the number of subsets of a set with \(N\) elements is \(2^N\). This is an exponential dependence! Now, since sperm whales have the largest brain among all animals, and due to the exponential relation, the distribution of consciousnesses among animals on earth is dominated by sperm whales, and all the others are negligible. If our goal is to bring to a minimum the number of suffering consciousnesses, we should focus on sperm whales.

Caveats etc.

-

Although I love thinking about consciousness, I’m not very versed in the literature. In particular, I don’t know if the ideas presented here are indeed new and supported by other theories and experiments. And my interpretation of the split-brain experiments might be immature. This doesn’t change the fact that I enjoyed coming up with the ideas myself.

-

I understand that we need to be more careful in how we define the distinctness of two consciousnesses. Also, I did not take into account the option of multiple consciousnesses “merging” into one when they come into contact and share information with each other.

-

In the sperm whale implication, I did not consider the difference in the “amount” of consciousnesses between whales and other animals. I believe that the exponential factor would dwarf any other factor, which depends on a reasonable measure of consciousnesses.

-

Please do not consider me as an advocate of this theory. It is not my view. It is just a theory, and I do not claim to support it over the alternatives.