My Failed Attempt to Crack RSA

As the first post of this blog, I thought I’d show an idea that I had years ago, when I was 17. I thought I had found a novel way to efficiently factor integers into their prime factors, using a device based on charges moving in magnetic fields, and therefore to crack the RSA encryption. As will be evident to you if you keep reading, this was very naïve, to say the least. I did not understand at all the idea of computational complexity, and I did not appreciate the immense magnitudes of the numbers used for RSA public keys. The method I had found is not only physically non-realizable and flawed, it also does not solve any aspect of RSA. Nonetheless, I do think it’s an interesting idea which combines basic math and physics. Since one of the purposes of this blog is to archive old thoughts and ideas so that they don’t fade into oblivion, I decided to post this.

So, here is the write-up I did for the RSA-decrypting idea, translated into English. Please note that I wrote (and illustrated) this when I was 17, and so it does not represent my current state of knowledge.

A Hypothetical Device for Finding the Prime Factors of a Number With Two Prime Factors

As is well known, no efficient method for finding the prime factors of a number with two prime factors is known. The RSA encryption system is based on this fact. In this paper I will present a hypothetical idea for a device that might be able to perform this factorization. I’ll start with two caveats:

-

My only scientific “qualification” comes from high-school. I don’t have an academic background, and so the level of this paper may be low. I’m apologize for this.

-

This idea may be impractical, or not efficient - I don’t have the knowledge to tell, and therefore I’d be happy to hear your comments.

The purpose of the device

Given a number \(K\), such that \(K=pq\) (\(p\) and \(q\) are prime numbers), the device will find \(p\) and \(q\).

The mathematical foundation

Given a rectangle, there is a method to find a square such that the area of the square equals the area of the rectangle.

(Figure 1. image taken from http://mathworld.wolfram.com/RectangleSquaring.html)

The rectangle is \(BCDE\). We will extend the line \(BE\) with \(EF\) such that \(ED=EF\). We draw a semicircle whose diameter is \(BF\). Now we extend \(DE\) until is intersects the semicircle (at \(H\)). We draw a square whose side is \(HE\). This square has the same area as the rectangle \(BCDE\). Proof:

\(\begin{align}

S_{BCDE} &= BE \cdot ED = BE \cdot EF = \\

& = (BG+GE)(GF-GE) = (GH+GE)(GH-GE) = \\

& = GH^2 - GE^2 = HE^2 = \\

& = S_{HEKL}

\end{align}\)

Q.E.D.

In fact, what we need to do is the opposite: given a square, to find the corresponding rectangle. For example, if we a searching for the prime factors of \(247\), we are actually searching for a rectangle whose area is \(247\). Of course, there are infinitely many such rectangles. We are looking for the rectangle whose side lengths are integers, in this case \(13\) and \(19\) (\(13\times19=247\)).

The physical foundation

In the hypothetical device I will use the Lorentz force, and so I describe it now.

The magnetic force acting on a particle with charge \(q\) moving at speed \(v\) in a uniform magnetic field \(B\) is \(qvB\).

(This formulation applies only when the velocity is perpendicular to the magnetic field, and I will refer only to this situation).

The direction of the force is perpendicular to both to the velocity and magnetic field, and is given by the right-hand rule.

Therefore, the magnetic force is a radial force, and the particle will move in circular motion:

\(qvB=\frac{mv^2}{r}\)

where \(r\) is the radius of the circular motion and \(m\) is the mass of the particle.

Description of the device

Now I will explain the idea behind the device. I’ll start with an example:

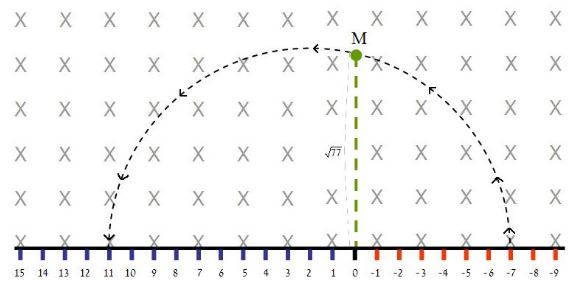

(Figure 2)

In this figure, the device is shown while factoring the number \(77\). From the red ticks (the negative integers, on the right) positive charges are fired upwards. In all of space there is a uniform magnetic field, directed into the page/screen. The charges are fired each with a different speed, such that they all pass through the point \(M\), which is at distance \(\sqrt{77}\) above the origin. On the blue ticks (the positive integers, on the left) there are detectors, which can detect the arrival of a positive charge.

As I will show soon, if and only if the charge was fired from a point whose distance from the origin is a divisor of \(77\), it will pass through a detector. This detector lies on a number which is a divisor of \(77\).

In the figure above, the charge fired from \(-7\) (\(7\) divides \(77\)) arrives at the detector at \(11\) (which is also a divisor of \(77\)). Thus we discovered that \(11\) is a divisor of \(77\), and through a simple calculation we can find that also \(7\) is a divisor of \(77\).

Note that charges are fired from all the red ticks (more precisely, from all red ticks less than or equal to \(\sqrt{77}\) other than \(1\)), but they do not arrive at a detector. Only the charge fired from \(-7\) will arrive at the detector, and from the position of the detector we can deduce the divisors of \(77\).

The same idea can be applied to other numbers we want to factor.

For the proof, let’s look again at Figure 1.

Lets assume that there is a uniform magnetic field, directed into the page/screen. A charge is fired upwards from point \(F\), in a velocity that will make it pass at point \(H\), and it arrives at point \(B\). From here we deduce that \(BE \cdot ED = HE^2\), and since \(ED=EF\) it follows that \(BE \cdot EF = HE^2\).

\(HE^2\) is the number whose prime factors we want to find (\(77\) in the example above), and is therefore an integer. Since we are firing charges only from points whose distance from \(E\) is an integer, it follows that \(EF\) is also an integer. Thus, if the charge arrives at \(B\) such that \(BE\) is also an integer, then the lengths \(BE\) and \(EF\) will be the prime factors of \(HE^2\).

Let’s look at the following figure:

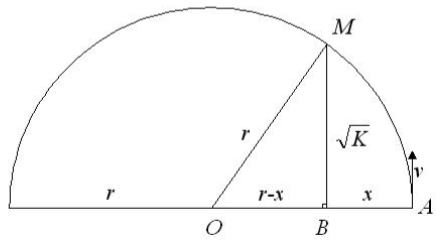

(Figure 3)

We fire a charge \(q\) with mass \(m\) from point \(A\). There is a magnetic field \(B\) pointing into the page/screen. We fire the charge from a distance \(x\) from point \(B\), and we want it to pass through point \(M\) which is at distance \(\sqrt{K}\) over point \(B\). We fire the charge upwards. We need to find the speed at which to fire the charge such that it will pass at point \(M\).

\(qvB=\frac{mv^2}{r}\)

So

\(v=\frac{qBr}{m}\).

From the figure and from Pythagoras’ theorem

\(MO^2=MB^2+BO^2\)

That is,

\(r^2=(\sqrt{K})^2+(r-x)^2\).

From this we get

\(r=\frac{x^2+K}{2x}\).

We plug this into the expression for \(v\) above and we get:

\(v=qB \frac{x^2+K}{2mx}\)

This is the speed \(v\) at which a charge at distance \(x\) from the origin should be fired.